The petroleum industry has very complex historical, political and economic factors. Over the past five years we have seen the oil price react to both political and non-political events such as decisions by OPEC, trade agreements or even the corona virus affecting Chinese demand. However, this Tip of the Month discusses the fundamental economic factors that determine the price of oil in the long term and the global standards for crude oil valuation.

In our industry there are three primary factors that determine the price of crude oil:

The first four items in the above list currently have the greatest effect on crude oil price. Reserves will only exert an influence on price when they are insufficient to support the desired worldwide production rate. Supply and demand must include both crude oil and petroleum products made from it. Crude oil quality reflects the products that can be refined from a particular crude oil and the cost to the refiner to do so. Location will determine the transportation cost to move crude oil and/or petroleum products from the point of production/refining to the customer. Reliability is controlled by production rate and productive capacity, while availability refers to reserves.

Politics and global events determine oil price in the short term; economics determines oil price in the long term.

It can also be said that productive capacity influences prices in the short term while reserves influence prices in the long term.

1. Market (supply/demand)

It should be realized that supply/price/demand are tied together as a package. It is impossible to change any one of these three without affecting one or both others. The relationship between supply and demand effects the price paid for oil and gas. Conversely a significant change in price will affect both supply and demand. At times it is all quite cyclical. For example, a major price increase commonly leads to an increase in supply as the result of additional drilling. The same price increase frequently reduces demand as various conservation measures are taken. The result is an imbalance of supply and demand, which may lead to a lower price.

Fig 1. Basic Supply and Demand Economic Model

The oil industry has experienced several of these cycles over the past 35 years. There are also marked seasonal cycles of consumption—heavy gasoline demand for summer driving and heavy home heating loads in winter—which must be anticipated in planning refinery runs months ahead of time. The gas industry experiences a semiannual cycle with peak loads in summer and winter and low demand in spring and fall.

The unprecedented price volatility which has occurred since the “price shocks” of the 1970s, and more particularly since crude oil began to trade as a commodity in the 1980s, has had a dramatic impact on the industry. The results have severely affected oil company profits, the revenues of oil exporting countries, and the availability of investment funds. This, in turn, has led to great ingenuity by the industry and the financial community in their efforts to manage price risk. Some examples are diversifying product and investment portfolios, investing heavily in R&D and integrating new technologies into processes such as the use of IoT.

Timing of available crude oil supply can be an important pricing factor. Imported oil may take more than a month enroute on the high seas, even more if the owners of the cargo choose to “slow steam” to conserve ship’s fuel, and perhaps to wait for an improved price at the receiving end of the voyage. The inverse can also occur in a declining market. This has led to extensive use of options and futures for price hedging for the longer haul crudes.

Longer range timing of available supply is also a principal factor in regard to the industry’s exploration program. High prices make funds available for new exploration. When prices plummet exploration is the first activity to be curtailed in order to preserve oil company profits under the western world’s system of accounting. The long lead times, five to ten years, between exploration and discovery and actual production imposes another almost irreversible cyclic factor into the equation. High prices beget increased exploration, and supply, which can easily exceed overall demand.

2. Location (transportation)

Since crude oil production and local consumer demand are generally far removed from one another, transportation is also a factor in setting the demand for certain crudes. Crude oil has been moved from the oilfield to refineries by wagon, truck, rail car, pipeline, barge, and tankship. Transportation costs vary with the means of transport and volumes. Political jurisdictions, and sometimes the physical characteristics of the crude oil, can also have an effect on its transportation. If there is sufficient daily volume over land pipelines are the cheapest method. Crude oil that can be moved in sufficient volume by pipeline will out-compete those crudes which have to be moved overland by other methods.

Pipelines require large investments, and once installed must be kept full, in order to realize their low throughput costs. In North America pipelines are probably subject to more governmental regulation than are the other forms of crude oil transportation due in large part to their having to cross so many tracts of individually owned land. In other parts of the world operating pipelines have sometimes been permanently shut down due to political problems.

The question is often asked, “Who pays the transportation cost for oil?” The obvious answer is the ultimate consumer of petroleum products as they pay all costs. But the more important question is “Who bears the burden of oil transportation costs?” The answer to that question is the oil producer. Because the price of oil into a refinery is determined by the quality of the crude and supply/demand conditions, not where it is produced. The wellhead price for oil is the refinery gate price minus the cost to transport it there. Houston, Texas is still generally considered the central location for worldwide pricing of crude oil.

3. Quality (refining cost and yield)

Crude oil quality reflects the products that can be refined from a particular crude oil and the cost to the refiner to do so.

A barrel of crude oil of itself is relatively worthless even though it will burn with a low smokey yellow flame. As a raw material, crude oil’s mixture of hydrocarbons, of greatly varying molecular weights, has great commercial value. The refining of crude oil into the hundreds of industrial and consumer products is hardly a cottage industry. Petroleum refining has to be done in sufficiently large industrial plants (called refineries) so that even the smallest product volumes can have sufficient economy of scale to permit the whole refining process to be economically feasible.

In the larger oil companies the internal value of each individual type of crude oil as a raw material is subject to intense study and computation by a group of experts. On the basis of laboratory distillations and statistical calculations these refinery engineers determine the optimum volumes and values of all the fractions of a specific crude oil, including, for example, such attributes as the octane number of its gasoline fraction and the pour point of its diesel fuel component.

The Value of Crude Oil as a Raw Material

There is no single benchmark pricing source for crude oil. The tremendous volume of trading in crude oils has evolved several major price references. These are Saudi Arabian Arab Light, West Texas Intermediate (WTI), Forties and Brent from the U.K. waters of the North Sea, Fateh from Dubai, and more recently the Urals-Mediterranean for the Russian production entering the western markets. Singapore quotations are also increasingly employed as a reference for crude oil pricing in the Far East.

The location of the production, its transportation requirements, and its eventual market also affect the value of a particular crude oil. The lighter, fairly sweet crudes of North America and the North Sea find favor in the American market where gasoline motor fuels have large demand. The heavier Mid-East crudes fit well into the Japanese product market mix.

Crude oil is considered a transportation fuel, because as much of 90% of it is used to power vehicles; namely gasoline, diesel oil and jet fuel. Modern refineries can make these products from almost any quality of oil, but the cost of doing so is greater for low gravity high sulfur crudes. Thus, there is a definite linkage between the price of crude oil, the cost of refining, and the price of transportation fuels.

Crude Oil Characteristics

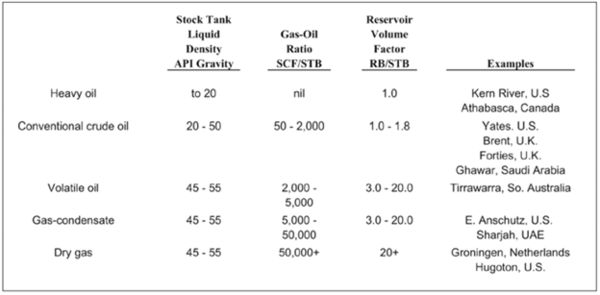

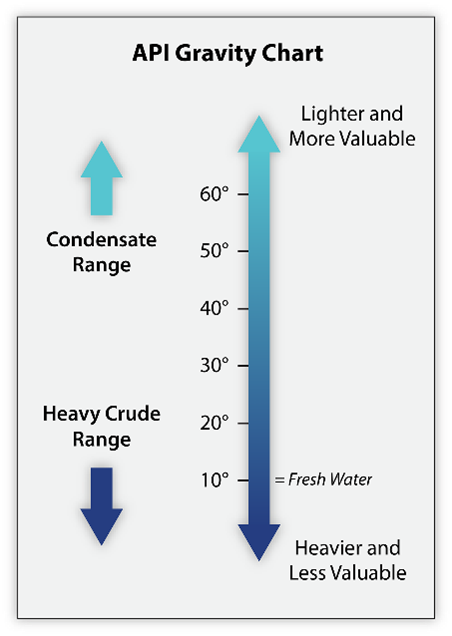

Although the geologist, geophysicist and petroleum engineer may tend to think of all crude oils as alike, the refining engineer knows differently. No two crude oils are physically identical. Table 2-1 summarizes some of these differences. Consequently, the products that can be recovered and manufactured also differ significantly from one crude oil to another. Lighter (i.e., higher API gravity) such as Norwegian North Sea Ekofisk tends to have more gasoline by volume than heavy crudes such as Persian Gulf Dubai Fateh which has proportionately more gas-oil (diesel) and residue cracking stock.

Table 1. Typical Reservoir Fluids Characteristics

Fig 3. API Gravity Chart example

Crude oils from different sources are categorized according to the API gravity (a rule of thumb index of the proportion of straight run gasoline to be expected), and the weight percent of sulfur incorporated in the crude. The sulfur imparts undesirable odor to the refined products and also increases their corrosiveness. A crude oil is classified as a “sweet” crude if it contains less than 0.5% by weight of sulfur and as a “sour” crude if it contains a greater amount. The price for a sour crude may be significantly less than that for a sweet crude of similar API gravity.

World Oil Pricing

Prices for crude oil in international trade are universally quoted in U.S. dollars per API barrel of 42 U.S. gallons at 60°F. The derivation of the 42 gallon measure goes back to the earliest days of the industry in Pennsylvania when oil was transported by wagon in used 50 gallon wine barrels. There was a good deal of spillage and the pattern of the trade was to pay for only 42 gallons at the destination without resort to further measurement. Producers soon learned to ship that way as well.

Some international statistics regarding production are quoted in metric tons. This method of measurement derives from Europe, where most crude oil has been received by oceangoing tanker, and weight (displacement) was an easier gauge. Conversion of one measure to the other requires knowledge of the density, or API gravity, of the specific crude oil. Actual monetary settlements are generally made in currencies other than U.S. dollars.

More and more often in the present state of the world economy, and most particularly in the developing world, settlements for crude oil imports may involve barter arrangements for exportable goods from the purchasing country.

The term “world price” occurs frequently in economic discussions of the petroleum business. This is a quite general term. In the eastern hemisphere it is often taken to mean the per barrel price paid for spot, or unscheduled tanker load purchases of crude oil in Rotterdam harbor. Elsewhere it may mean the OPEC posted price for “reference” Saudi Arabian light crude. In several oil-importing industrialized countries “world price” may refer to the actual, or historical cost of the average imported barrel of crude oil into that country. For the first seventy-five years of the industry, after the Drake well in Pennsylvania, the prices of domestic North American and overseas crude oils each demonstrated a high degree of stability and similarity.

To learn more about crude oil pricing and petroleum economics, we suggest attending our Expanded Basic Petroleum Economics course.

References

1. Ball, Max: “This Fascinating Oil Business” 1949, Bobbs-Merrill Co., New York